The Reference Trap

A closer look at how references went from inspiration to imitation and how to reclaim originality in an oversaturated visual culture.

Hi everyone,

You all must know by now my frustration and slight obsession with the current visual culture, working with clients who struggle to understand a visual that doesn’t exist yet. It’s a constant fight of wanting to create fresh work, but having difficulties to get it approved. I’ve recently started sharing updates on how I am building an offline image archive, turning away from Pinterest, Are.Na and Cosmos for personal projects and diving into collecting trinkets, folders, memories and scan them in for my personal archive. The recent post ‘We Are All Image Directors Now’ and ‘Fashion Doesn’t Need More Content’ have been a research project of mine, from that newsletter and my personal experience I started gathering a lot more information and point of views of things happening in the industry.

Building an Image Archive in 2025

In a sea of sameness, the best references are the ones that ask questions, hold tension, and outlast the algorithm.

Fashion Doesn’t Need More Content

Endless drops, empty metrics, and the burnout of image-making in a content-obsessed industry.

Moodboarding has become second nature to everyone. Every project begins with a deck of references. But when the same fifty images keep resurfacing we have to ask: are we researching, or just recycling?

I’ve sat in feedback sessions at art and fashion schools where five different students presented nearly identical decks, built from visuals I first saw more than a decade ago in my own college years. The sameness has become so normalised it barely registers. Fashion design students are taught to dig into archives, materials, and process. Image-makers, especially in the field on fashion marketing, meanwhile, are rarely pushed to treat research as a craft of its own. Yet knowing how to source, read, and transform raw images into something stylised is an art form and one that’s slipping away.

How we got here

The rise of platforms like Pinterest, Are.na, and Instagram has reshaped how creatives build ideas. Instead of digging through books, archives, or harder-to-find sources, research became as simple as a search bar. But algorithms don’t surface what’s rare, they surface what’s already popular. The same fifty pictures rise to the top, over and over again, creating an endless feedback loop: yesterday’s campaign scan appears on ten moodboards today, then shows up again in tomorrow’s shoot. What begins as inspiration quickly mutates into imitation, and because the cycle is so constant, it rarely gets questioned.

To search is to inherit a worldview. If your archive begins with a search bar, your work begins with someone else’s bias.

Schools have only reinforced this shift. Especially in fashion marketing courses, referencing is framed as a way to validate taste and show your thinking rather than challenge it. I’ve seen whole classes present decks that mirror one another, as if originality is less important than recognition. And once moodboards became client-facing deliverables, the issue deepened: references stopped being private tools to test ideas and instead became a performance of alignment, something to reassure nervous stakeholders that the outcome would look familiar. In this reference economy, research has lost its edge. What could have been a way to push culture forward has been reduced to a cycle of recycling and getting us stuck in the cycle of sameness.

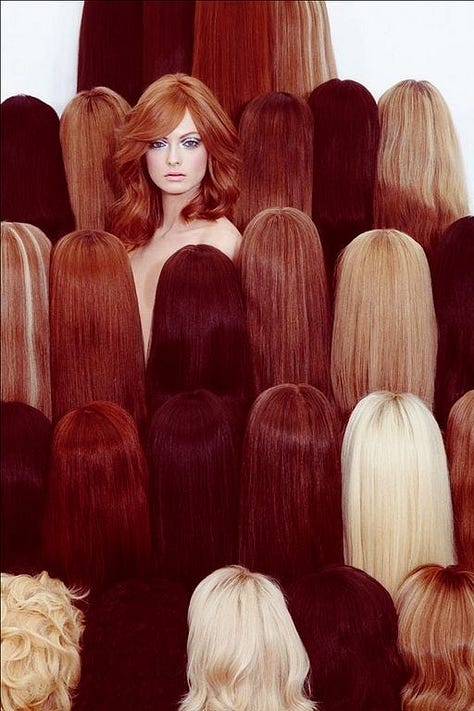

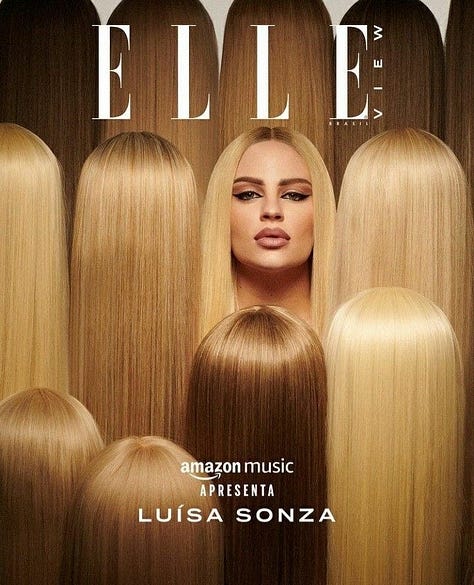

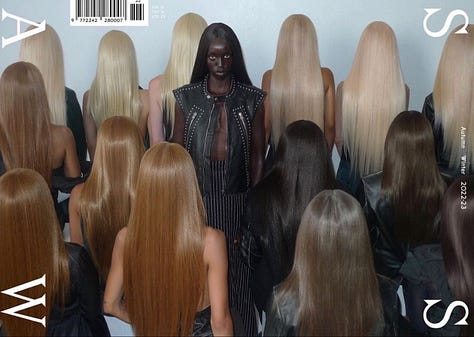

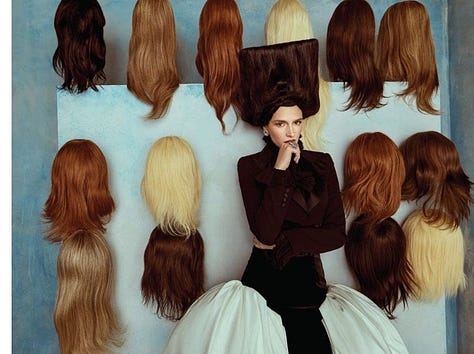

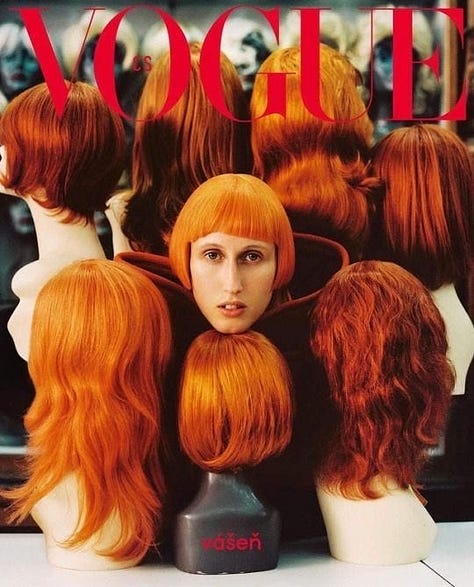

*Individual credits are omitted intentionally, the focus is on the repetition of the image, not on calling out specific photographers.

The Consequences: Beautiful, Boring Work

The result of this cycle is a visual culture that feels polished but strangely hollow. Aesthetics are optimised to perform, but they rarely surprise, provoke, or move. What once signalled a point of view has become a default setting. You can scroll through campaigns from global fashion houses to emerging labels and find them indistinguishable, because the references are the same. But the brands are all starting to blend together, even if it didn’t start like that initially.

Clients have only deepened the dependency. Before approving an idea, they want to see the references, sometimes even before hearing the concept itself. The reference becomes the proof, the comfort blanket, the way to sell in an idea to stakeholders who fear risk. But when the proof is always something already familiar, the outcome can only ever be a variation of what we’ve seen before. The cycle produces work that is technically beautiful yet emotionally flat, caught between safety and sameness.

For young creatives, the pressure is even bigger. It’s easier to point to an existing style than to propose a new feeling, especially in an industry where budgets and timelines leave little room for experimentation. The result is a generation fluent in the language of referencing but hesitant to step outside of it. You see it in the flood of “editorial” shoots on Instagram: tasteful light leaks, contorted poses, archival filters as an example, all of which mimic the surface of experimentation but rarely carry the substance of a new idea.

The Fear of the Unknown

Perhaps the biggest consequence of the reference trap isn’t sameness itself, but the fear it has bred. In today’s industry, originality has become a liability. Presenting unfamiliar research, images that don’t already circulate online, or visual worlds that don’t resemble last season’s campaigns, ‘raw’ visual research before stylised elements are introduced, can spark hesitation and fear rather than excitement. Clients worry about how something untested will perform. Stakeholders, under pressure to guarantee results, default to what feels safe.

This has quietly reshaped the creative process. The creative process used to be a space for exploration, but now moodboards have become safety nets. They exist less to spark a team’s imagination and more to reassure decision-makers that the outcome will land in familiar territory, which is honestly sad for art directors because that used to be the most exciting part. As a result, ideas are often reverse-engineered from references. Before that references used to be tools to enrich an idea.

"The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled." - John Berger, Ways of Seeing (1972)

The irony is that this fear stifles the very thing brands claim to want: differentiation. By leaning on references as proof, they limit themselves to echoes of what already exists. And for creatives, the lesson is clear, stick close to the familiar, or risk losing the room. The unknown, once the most exciting part of image-making, is now seen as the most dangerous.

Beyond the Algorithm

If the problem is oversaturation, the answer won’t be found by scrolling deeper into the same feeds. Online archives have their value, but they’re built on repetition. Algorithms surface what has already proven popular, which means the same scans, the same photographers, the same Western-centric aesthetics dominate. For years, whole generations of creatives have been working from this recycled pool, mistaking visibility for relevance. What’s missing are the images that don’t fit the algorithmic mould: materials tucked away in out-of-print books, regional magazines, overlooked cultural archives, or personal collections that haven’t been digitised. These rarer sources carry different textures, contexts, and histories, they hold the potential to unlock new visual languages because they haven’t already been rinsed through a thousand campaigns.

Building an offline archive is about reintroducing friction into research. It slows the process down, forces you to sit with images, and allows connections to emerge that a search bar could never generate. In this sense, archiving becomes an act of resistance. Resistance against sameness, against algorithmic bias, and against the idea that originality can be found in what’s most easily surfaced.

Rethinking Research

If image-making is to move forward, research itself has to be reframed. It can’t remain a matter of collecting what looks good together on a slide. The point is to look for what interrupts it. Research at its best is digging for undercurrents: overlooked symbols, overlooked artists, gems in history, overlooked media. It’s about training your eye to notice what feels unresolved, then finding ways to translate that into something intentional.

This is also where the responsibility lies for those working with brands and clients, including myself. I feel bad and guilty contributing to this cycle when delivering yet another client project that has been made safe through endless rounds of approvals. Referencing shouldn’t be a way to pre-approve sameness, but a way to expand the field of possibility. When research is used as a provocation , it creates space for new aesthetics to emerge. The challenge and the opportunity is to shift research back into an engine of originality, one that informs the work without predetermining its outcome.

some posts you might like

The Way Forward

Originality won’t come from abandoning references altogether, but really from changing our relationship to them. Offline archives, personal collections, even fragments from outside the visual field, these are ways to disrupt the loop and make space for work that feels alive again. We shouldn’t put the appearance of a deck first, we should think a lot more about how deeply the images have been read, questioned and transformed and how it relates back to the concept and insight. What the original artist had in mind, or what culture it is from and their message and what it stands for. It’s also a way to avoid cultural appropriation, because the inspiration is coming from its depth and actual research and not just from an aesthetic that is being used.

In a culture saturated with repetition, choosing to research differently is itself an act of resistance. It’s slower, harder, and less predictable, but that’s precisely why it matters. The reference trap only holds power if we stay in it. Step outside, and image-making becomes what it was always meant to be: not a collage of what we’ve already seen, but think of it as a proposal for what we haven’t yet imagined. If more of us start doing it, perhaps one day this cycle breaks. It can’t continue for eternity, that’s for sure.

Love,

Zoe

The Art Direction subscribers chat is available for every free subscriber. If you have any questions, please drop it in there and I will answer you, try to help you or write requested articles. You can also always message me on DM or Instagram.

If you’d like to support my Art Direction newsletter and help me keep dedicating time to writing and sharing more insights, you can buy me a coffee. Every bit of support helps me stay focused on creating content I love and bringing fresh ideas to you. ❤️

Follow Art Direction on Instagram for inspiration on your feed.

"The cycle produces work that is technically beautiful yet emotionally flat, caught between safety and sameness" 🥲🤌🏾This piece hits the nail on the head and definitely speaks to what I've been feeling for quite some time now (especially every time I see the latest food inspired beauty drop). Unfortunately I think we've reached an exhausting stage now where most people can't even be bothered to search for the OG reference and are ok with just regurgitating the latest interpreted version of it from others. This was so good and I'll def be coming back to this piece again

I love this. I think the deeper issue (deeper than online vs offline references) is that you should start with an IDEA. You see that with Tim Walker. That's just one concept but it could be for a brand or a collection or whatever. The idea is not an image. It is a thought. Something you want to convey. Only when you are clear on that do you go hunting for images to convey it (or words, or choreography, or whatever your medium of communication is). The issue with online culture is that it's made it so easy to find images and shows something that LOOKS good that people just reach for those. And processes have sped up so much there isn't time to develop an idea, a world, a thought - and THEN figure out how to communicate it. It's such a shame and it makes for such hollow work. The brands that buck this trend stand out so clearly. Vacation Sunscreen, Rochambeau Club...